In November 2022, Tomme Arthur did something unusual for a brewery owner. He spoke about his future plans and how, in that future, his brewery looked smaller.

First reported in San Diego Beer News, The Lost Abbey’s plan was to downsize by selling their 30-barrel brewery – 35 hectolitres, give or take – and renewing their lease with less floor space.

“My partners and I understand that our future is great, but we’ve got to get smaller in many areas of our operation,” Tomme told San Diego Beer News at the time.

“It’s hard to mow the lawn with a tractor when a standard walk-behind model is better. Sure, it’s doable … but not really effective.”

It was news that immediately cut through the American craft beer industry, rapidly appearing in different publications and shared widely across social media. In the months that have followed, Tomme has been on the front cover of the Brewer’s Association’s magazine and a regular guest on podcasts to talk about his and his business partner’s plans and the thinking behind them.

Tomme is a widely respected brewer who has been making beer since the mid-1990s and, while The Lost Abbey isn’t a large brewery, they are highly regarded. Their beers have long been sold in multiple states; among them are some of the finest Belgian-style beers and big beers in America. Sibling operation Port Brewing make West Coast IPAs that have long been praised in a part of the world that perfected them.

When we catch up at one of The Lost Abbey's venues, Tomme (pictured above) tells me he believes the attention attracted by their future plans has been driven by the honest way he spoke about running a beer business at a time when the business of beer feels different to any other time.

“I really wanted to approach it with an authenticity,” he says. “Because there was a point in time where we weren't going to make it, and it was going to take a lot of work, and that work was going to need to be very thoughtful.”

In a time of economic uncertainty, when the cost of ingredients, goods, rents, labour and everything else – or so it feels – has been going up, others soon reached out.

“I think we became advocates for the conversation and we certainly got a lot of people who said, ‘Thank you very much for the authenticity, for the honesty and for coming out saying it.'

“It wasn't courageous; it was real and I think real is important.”

WILD TIMES

It was mid-May when I dropped into the San Elijo Hills to talk to Tomme. Located on the outskirts of San Marcos, it’s a planned community that feels a little like it’s been plucked from Arrested Development although it’s far more complete than anything with Bluth fingerprints attached.

Tomme and I joke that I might be the first person in town that doesn’t live or work here, a point driven home by my Uber driver, who lives 15 minutes down the road yet becomes entirely disorientated as soon as we hit the perfectly-designed town square.

It’s home to one of three satellite locations for The Lost Abbey and is a space that explains the brewery’s shift in gears. The brewery’s original San Marcos home is one they took over from Stone Brewing after they moved into their impressive Escondido location, Stone Bistro World & Gardens.

The 30-barrel brewery had fermenters four times that size. It meant they could make a lot of beer, but what they lacked was the ability to make smaller batches for their bars.

“We could create innovation if we had places for it,” Tomme says, “but that was a big part of why we announced that growing down was important because size was killing us with regard to flex. In a hospitality environment, you need that flexibility in order to create new draw.”

They opened the first taproom away from the brewery in Cardiff in 2015; San Elijo followed in 2019 with another opening in downtown San Diego in 2021. It's an approach that fundamentally changed what they were doing.

“Eight years ago, I had one tasting room environment and it was at the brewery,” he says. “I didn't have auxiliary rents, multiple different landlords, and multiple different utility beers. So, all of it is exponentially more work.”

But each venue has developed its own customer base and, while Tomme says they’re all supported by their community, using San Elijo as an example, locals want to see new beers. As such, the business has changed quite dramatically since 2015.

“One of the things that came out of our conversations as we looked at our struggles and our financial realities," he says, "was that, a few years ago, we became much more hospitality focused.”

Although selling your own beer has its advantages when it comes to capturing the most value from each keg, Tomme says it’s a business model that isn’t so straightforward, particularly in California where rents and wages have been rising fast.

“The running of a satellite location is not as cheap as people make it out to be: the cheapest beer to sell is the beer that never leaves your building,” he says.

“We used to sell a lot of beer to one wholesaler and they’d back up a full truck, load the truck at the brewery, and then we’d get a giant cheque. Now someone at one of our bars has to put a beer order in, someone at the brewery has to fulfil it, and then you have to decide if you can fulfil it, then ship it and do all the paperwork.”

While plenty of breweries do open with a hospitality focus, it isn’t always so simple. Small brewers like to take chances, be flexible and innovative and, at times, opportunities present that you know you should take.

“It is a battle because for a lot of people it's frog in the pot,” Tomme says. “You don't necessarily think about it – it’s all of a sudden, you're doing it.”

The Lost Abbey will still have a hybrid model where they run their taprooms and send beer elsewhere, but their smaller size gives them the flexibility to brew beers that will keep drawing people into their taprooms.

Since announcing their plans, further changes have followed. Pizza Port Brewing took over the San Marcos site and absorbed The Lost Abbey's sibling operations Port Brewing and The Hop Concept. The Lost Abbey’s production moved to nearby Vista, to a site run by Mother Earth Brew Co under what’s known in America as an alternating proprietorship model: Mother Earth own the brewing equipment and The Lost Abbey lease it from them to make their beer.

“For the most part,” Tomme says, “we’re in the driver’s position because we’re the only other tenant and they’re not expecting to make much beer there. So, it’ll be us controlling the space on our schedule, and we’re ready to open a taproom in that environment.”

Historically, he’s viewed increasing the amount of beer they sell as a way to make the business more profitable – the thinking being the more you sell, the better off you are – and it’s a point he’d often pushed within the business.

“You can grow the sales but if it doesn’t have any margin, then it’s just going to cost you,” he says.

“So we said, 'We're not going to go on with this the way we've always gone about it', which is bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger. Bigger is not going to fix this."

The need for brewers to consider an alternative approach are compounded by the current economic climate. It's one in which Tomme believes that, for at least the next year or two, owners need to batten down the hatches.

“You could put a stake in every single continent that makes beer and I think the issues are quite similar and not disparate. Beer isn’t immune to a global evolution or the global crisis right now where money is expensive, barley is in shortage and aluminium is expensive. It’s a wild time.”

THE SLOWDOWN

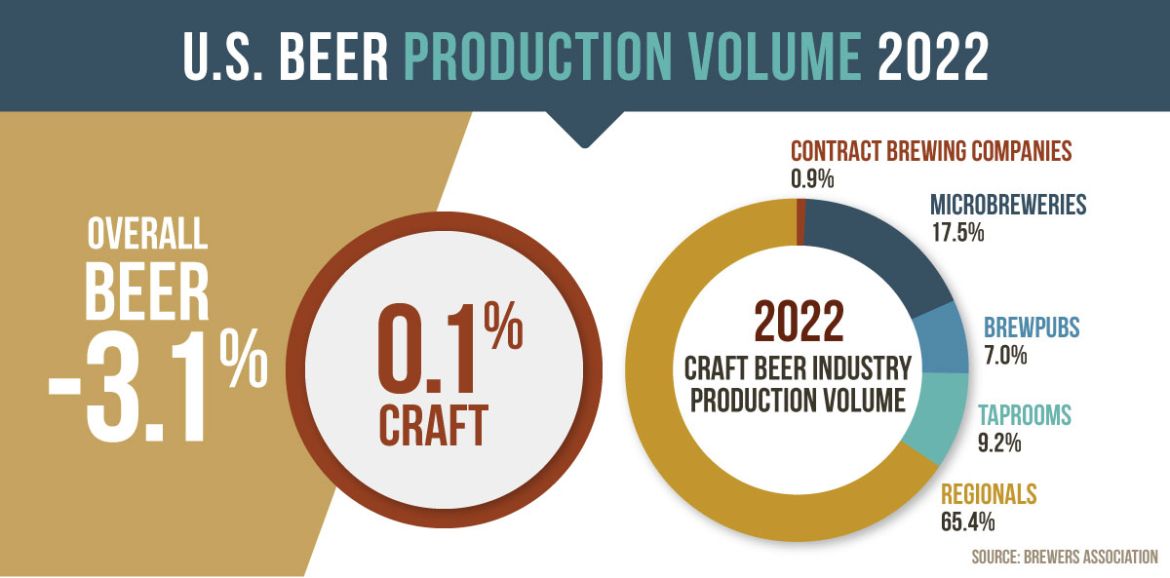

The future growth – or lack thereof – for craft beer in America was a major talking point at the Craft Brewers Conference in Nashville. In his keynote address, the Brewers Association’s (BA) chief economist, Bart Watson, said that, according to their latest Beer Industry Production Survey, craft beer production in 2022 was the same as in 2021 and that’s with brewery openings still outpacing closures.

Taking a longer view, he said the average annual growth in craft beer since 2017 was 1.2 percent.

“Those years of double-digit growth are clearly well in the rearview mirror,” Bart said. “And unless something changes, I don’t think we’re going to see them again anytime soon.”

The annual growth rate of larger breweries defined as craft by the BA (which excludes those owned by multinationals) looks particularly concerning; Bart says regional brewers saw a two percent decline and microbreweries (those that make 17.5 thousand hectolitres or less a year) were up by just one percent, a rise due their focus on draught over off-premise sales.

The positives could be found in those breweries led by hospo: brewpubs and taproom production was up a combined seven percent. However, Bart added that much of that growth came from places that had opened since 2018, which showed the need to remain new and innovative.

“Even in this category,” he said, “which is clearly the bright spot within craft, breweries are going to have to work to reinvent to stay competitive. More breweries are still coming, we're going to get more openings, and more business concepts are going to enter the market.

“I think there are challenges on the horizon for breweries of all sizes. And we're all going to need to reinvent going forward if we want to grow.”

Although Bart’s data showed that more breweries opened in 2022 than closed – 529 compared to 319 – he said that trend was coming to an end, and that the number of new openings was the lowest since 2013.

“The era of everyone opening and no one closing, though, is clearly going away. When you look at these graphs, it's pretty clear that they're coming together.

“That's normal. Most industries have roughly openings and closings in balance. What has been abnormal is the last ten years, where everybody opened and almost no one closed.”

We've seen echoes of this in Australia, with the frequency of voluntary administrations rising quite dramatically, both in regards to beer businesses and throughout the economy.

HISTORY REPEATING?

Years ago, craft beer’s position as a growing part of a shrinking overall alcohol pie was held up as one of its greatest successes. People wanted more flavour in their beer, they were drinking less but drinking better, and craft beer was growing against the odds.

But Tomme says one of the key messages to come out of CBC was that therein lies the issue: craft beer is part of a shrinking pie.

“I think the biggest takeaway that people generally need to hear is that beer has been declining for a long time,” he says. “It’s not just us, it’s all beer.”

He's well-placed to comment: Tomme has been making beer professionally since 1996 and joined the Pizza Port team the following year. They were glorious days for beer in San Diego, with Coronado Brewing and Ballast Point both opening the same year Tomme started brewing, which was just a year after AleSmith opened.

Across America, the craft beer pie was tiny but growing, Sierra Nevada and Sam Adams had become major brewers and things were looking good. Money was pouring in, people felt they could open, and the demand would be there. Then, suddenly, breweries started closing.

So does it sound like history is repeating today?

Tomme argues the current economic situation is fundamentally different compared with the last downturn because there was still a growing consumer base for craft beer back then.

“At that time, there was not an educated consumer, so the snap came very differently because people built the wrong business," he says. "But when the consumerism caught up to the right business model, everything was available to everybody, because there was so much interest in it.”

He believes this downturn goes further because the beer consumer is fundamentally different.

“The snap is now coming because people are drinking less beer, and the people that used to be our apex customers still are drinking beer but now they're much older so they're consuming less.

“And then the generation of drinkers that we're coming into are – as Bart likes to call them – omnivorous. They drink everything, they’re not brand loyal, beer isn’t necessarily their first choice, and some of them don’t drink at all.”

During his presentation, Bart pointed to how broad the alternatives to beer have become and how much better they are at appealing to younger drinkers. By comparison, Millennials becoming old enough to drink had been a good thing for craft beer.

“We saw Millennials come of age and they loved craft, they moved into craft, they increased our demographics,” is how Bart put it.

“I think one reason that we're seeing overall craft stagnation is that's not happening as much anymore. We have new, different generations that have different preferences and are maybe more concerned about moderation as well. Unlike past generations that have moved into craft, I think we see the new generation of drinkers generally moving away from craft’s demographics.”

A SMALL FORTUNE

The need for craft breweries to think small is something Sam Holloway has been advocating for a long time. Since 2014, the Portland-based university professor has run Crafting A Strategy: an educational resource dedicated to supporting small breweries.

We last interviewed Sam in 2020, at which time he outlined his vision for craft beer and how he works with breweries. He believes today's market is particularly challenging due to competition still growing from new entrants and the dominance of the largest players on both supermarket shelves and through distribution, with America's model differing significantly from Australia’s.

“I would say that the top 200 breweries in the United States are all struggling,” Sam says. “And if you're trying to emulate their business model, you are going to struggle a lot more.”

With the greater resources available to the largest American breweries, combined with the fact smaller brewers aren’t cutting through on shelves, he says it’s hard to see how the model can really work, particularly for new entrants.

“I think if entrepreneurs have the ambition to grow and become, say, a $30 million company selling beer nationwide, they better start out rich.

“I think if you want to make money in the beer industry in America, and I think this is true in places like [Australia] too, you have to think small to get big.

“I know that's sort of clickbaity or like a catchphrase, but if you think big and make a big bet on yourself, then you're putting yourself at tremendous risk.”

He thinks The Lost Abbey’s decision to downsize connected precisely because a lot of other brewery owners felt the same way but had assumed Tomme was doing well due to the brewery's history and the prevalence of his excellent beer.

What's more, other brewery owners have seen that writing on the wall that can come with spreading yourself too thin.

“They’ve just said, ‘I don't want to be in this business. I still love beer and I love brewing, I'm going to change my business that allows me to do those things that I love and make a decent living. But I have to come to the grips that I’m never going to be in every grocery store in the country and, actually, I probably shouldn’t want to be.’”

He still sees a pathway to growth for smaller breweries through operating multiple venues, even if that presents its own challenges. The multi-venue approach means you can spread a team across multiple income sources and lessen the risk of each; they’re the kind of lessons he has learned firsthand through the brewery he part owns, Oakshire Brewing.

“In our biggest year, we produced 11,000 barrels and lost money,” he says. “We're going to make 4,000 barrels this year, basically one-third of the production of our peak, and we're much happier. We're stable, we're having fun, and we opened a pizza restaurant that’s doing well.”

He suggests that one of the challenges larger independent breweries face is a succession plan. There’s only ever been a small number of potential buyers for breweries with systems measuring 50 hectolitres and above; now, with the major players owning a lot of breweries and craft brands, there are even fewer suitors.

“There might be 50 companies globally that could see value in that," he says. “But neighbourhood restaurants have been around forever and continue to be around.

“A very profitable neighbourhood brewpub is a much more attractive investment than making a bet that the market is going to continue improving on a huge factory.

“I think that's the reckoning that a lot of brewery owners are going to have to face in the next ten years.”

For all that, he still envisions a positive future for craft beer. He’s long questioned the Brewers Association’s data on growth due to their exclusion of craft breweries owned by multinationals – the likes of New Belgium or Golden Road, who have pushed craft beer into new spaces.

“There are more people drinking IPA and full-flavoured beer in America now than ever before,” he says. “We're actually in a pretty attractive place for people using their money during drinking occasions to spend more, whether that's on beer or that's on wine and spirits.”

The wider beer category also has plenty of opportunities to speak to newer generations of drinkers due to its lower ABV when compared with wine or spirits.

“That's a way for us to bring in new drinkers to beer," he says, "to bring in young people that are health conscious when they realise the beautiful social aspects of having a pint with somebody and talking over your differences.”

He also believes there's another factor at play in the number of sales and closures: in some cases, it's driven by the length of time owners have been in the industry. Given the last downturn was more than two decades ago and a lot of breweries have opened over that time, there are a lot of founders looking to change careers.

“I don't think it's doomsday necessarily,” Sam says. “I think, for example, in Portland, a lot of the reasons breweries are closing is just because of retirements.

“I don’t think we’re going to have rampant closures of brewpubs and small breweries. But I do think we’ve reached the end of small breweries becoming big.”

ALES & TALES

Sam's belief in this pathway to growth is mirrored by Tomme; he says brewery owners need to keep reassessing their business, the beer market, and their position within it.

“I really wanted to tell people that if you’re not thinking about your business differently, then you're really probably not thinking about it correctly,” he says.

“So many people in this business are in the position they're in because, when they got in, growth was everywhere. I won’t even say growth was possible, growth was guaranteed. If you opened and you had a decent enough plan, then growth was at your front door.

“But nobody had to plan for no growth and now that’s what we’re being told to do.”

Personally, he’s excited to have more control over the telling of their story to drinkers, talking to them about The Lost Abbey's complex beers that often take so long to make or the IPAs that are passionately designed with decades of experience.

He still believes craft beer has the ability to attract new drinkers and excite existing ones through education and hospitality; in the case of The Lost Abbey, that education includes dipping into a huge library of delicious vintage beers that form the brewery's history.

“I think what's going to be more liberating for me is personally connecting the dots on a lot of the stories that we stopped telling,” he says. “It’s our story and we have the capacity to tell you why we're still here – and the reason we’re still here is because we made all these things along the way that people found great.”

He points to the glass of Peach Afternoon in my hand: an oak-aged blonde sour featuring peaches and white tea. It was the first beer he poured me at the San Elijo Hills taproom as he spoke excitedly about how it was made.

The conversation has been long, thoughtful and has covered just about every concern that being in the business of beer in 2023 raises. But there's a heady joy in talking to Tomme about something beautiful as he hands me bottles to put into my luggage ahead of a long flight home.

“That’s just amazing and it didn’t exist five years ago,” he says of Peach Afternoon. “So that’s what I want to hang my hat on: the future of our company is making meaningful and impactful beers. Like we’ve always done.”

You can read all of the articles from Will's travels and interviews in the US here.