Want to learn more about how beer is made, what it's made from, and how different processes can change the beer that ends up in your can, bottle or glass? The Crafty Pint's Beer Basics is here to help, as we work with experts from the beer industry to present the sort of information that will help you become a better informed and more engaged beer drinker in a manner that doesn't shy away from the technical but shouldn't scare away newcomers either.

In Part I of our look at yeast with Nic Sandery of Molly Rose, we addressed the most common forms of brewer's yeast and how they help create many of the beer styles you know and love. In Part II, things get a little funky...

Non-Conforming Beer Fermentations

OK, things are about to get a little weird over here. Having said we wouldn't scare away newcomers, here we are opening with the sub-heading: "Non-Conforming Beer Fermentations". Makes you want to dive straight in, right? But don't worry: Part II of our look at the magical world of yeast will all make perfect sense by the time you reach the end of the article…

Whereas in Part I we looked at the sort of yeast strains most commonly used in the brewing of beer, here the focus is on the yeasts – and bacteria – which make up a teeny, tiny, minuscule segment of the commercial beer. For all that they're featured in such a small percentage of beers, they’re typically found in some of the most romantic, exotic, and extensively written-and-talked-about beers on the planet. What’s more, scientific and anecdotal information about alternative beer fermentation microbes has really blasted off in the last decade and I for one couldn’t be happier. I love this stuff.

First off, we will run through some off-kilter fermenters that can be used to make beer that would semi-recognisable as beer to your nan while using techniques and fermentation times that won’t raise red flags with the bean counters at your local brewery.

Saccharomyces Farmhouse Beers

These beers only just missed out on being included in Part I, and they are Northern European and Scandinavian farmhouse ales.

The brewing techniques used with such beers are also non-conforming, using wood, twigs and botanicals to spice the brews, but that’s not what we're here to talk about. We are here to talk about the yeasts involved.

The most common commercially available of these is kveik. These yeasts can ferment a normal 5 percent ABV beer at temperatures greater than 35C in just 24 to 36 hours when pitched at less than one-eighth of the concentration of regular yeasts. To put this in context, if you plan to ferment a 5 percent ABV beer featuring exactly the same recipe of malt, hops and water with a standard Saccharomyces yeast – for example the US-05 strain found in many pale ales and IPAs – it would take on average six days for the beer to be reach the same stage: fully fermented and ready to be packaged. Little wonder kveik strains are sometimes referred to as super-yeasts.

What is stranger still is that when the yeast is dried out gently it can be stored as a flaky powder for six to 12 months without losing any of its crazy efficacy. It truly is a powerhouse and something brewers will be looking towards more and more as the environmental cost of brewing using traditional yeast and techniques with extended refrigeration requirements is further called into question.

For more on kveik, check out Mick Wüst’s two-part feature here.

Lactobacillus

Lactobacillus is the most used of brewing bacteria. This is the bacteria that provides the sourness in your yoghurt as well as your kettle-soured beer. In the right conditions, lactobacillus can sour a beer in as little as 12 hours. When allowed a little more fermentation wiggle room, “lacto” can slowly sour a beer as it ages over several months, a process that builds in a layered, complex and sometimes fruity sourness.

As with Saccharomyces, lacto comes in varying strains, all of which thrive in different conditions and produce differing flavours and levels or impacts of acidity as well as flavour profiles from lemon to guava.

NB Not to be confused with lactose, or milk sugar, which is used for very different reasons, as we explored here.

Lachancea

This is a yeast that has taken off with a blast. Lachancea is a cousin of Saccharomyces that ferments regular beers over standard periods of time but with the added benefit that it can also produce lactic acid in the same way that lactobacillus is used in sour beers.

The advantage of this is that brewers don’t need to worry about introducing bacteria – and possibly infecting other batches with said bacteria – when they’re making a sour beer. By varying the additions of dextrose (a simple sugar used in many beers) in a recipe, brewers are able to use Lachancea thermotolerans to produce lactic acid and drop the pH to as low as 3.1pH (an enamel-stripping level of acidity) in several weeks.

In simple terms, the more dextrose a brewer uses in their recipe in conjunction with Lanchancea, the stronger the tartness in the end product.

Now we get into the types of beers that are more artful than science-driven. These beers and the micro-organisms in them require a far more delicate touch and a much longer time to develop into delicious beer. These beers are also far removed from your standard pint of lager at the pub.

Spontaneous Fermentation and Wild Captured Yeasts

A spontaneous ferment refers to one started with nothing but natural, ambient microbes – in other words, those in the atmosphere around the tank or vessel containing the brewer’s wort – and without the addition of a commercial yeast or a harvested yeast pitch.

Lambic is the most famous spontaneously-fermented beer and is only made in the region around Brussels in Belgium. Most brewers producing such beers outside that region won't call their beers "lambic" out of respect for the traditional brewers, hence why you’ll sometimes find Australian brewers referring to “lambic style ales” or “pseudo-lambics”.

Of course, if you see the word “spontaneous” you might imagine something instantly (spontaneously) becoming beer. But, nah, that’s definitely not the case here. Far from it in fact.

During the brewing season for such beers, wort is produced by the brewer, placed into a broad shallow vessel called a koelschip (coolship) and left open to the elements for the night air to blow across and cool down the wort to fermentation temperatures.

The brewing season is the period each year in which the overnight temperature is deemed perfect for dropping the wort from boiling temperatures to those suitable for fermentation in the right amount of minutes and hours so that only the desired microbes fall into the wort to – hopefully – create the most delicious spontaneous fermentation.

Since the re-popularisation of lambic, inspired brewers around the world have started investigating the impact of their local microbial flora by using koelschips and similar vessels. While brewers in the USA have been leading the way, a number of Aussie breweries are dabbling with great success. Some have experimented with such fermentations during warmer seasons too; after all, in the world of 21st century brewing, rules often seem to be there only to be broken – or, at the very least, bent.

Spontaneous fermentation can also be started by microbes resident on fruit, such as wine grapes/must, as well as flowers or foliage. By either using microbiological techniques or just repeated small batch brewing using such fermentation-starters, an enterprising brewer is able to work with a whole range of wild yeasts existing all around us, all the time. These yeasts can have amazing characteristics and make unique delicious beers. Lachancea, for example, was originally found buzzing around inside wasps.

For more on this style of making beer, check out The Wild Ones.

Brettanomyces

Historically, Brettanomyces played an important role in both the fermentation and flavour profile development of beers. However, ever since Louis Pasteur discovered that micro-organisms were responsible for fermentation, they were subsequently isolated by commercial breweries for single organism fermentation, the less domesticable (if we’re talking about funky yeasts, we’re allowed to use funky language, right?) Brettanomyces was left by the wayside.

More recently, Brettanomyces – or to use its common abbreviation: Brett – has received a lot of bad press due to its presence as a fault in poorly-made wine. The common complaints on such occasions are flavours and aromas of horsey, horse blanket, band aid, rubber and sometimes faecal characteristics.

I tend to agree that these are not things I want in my wine or beer, yet when the correct strains are used intentionally in the correct way, Brett can produce amazing complexities of flavour: from savoury earthiness and forest floor through to pineapple, citrus, cherries, berries, honey, mint, aniseed and many others.

This is dependent on both the strain of Brett employed by the brewer as well as the conditions in which it is metabolising – metabolism being the chemical processes that all living cells undergo to turn food into energy. For example, a Brett strain could be used as the sole primary fermenter in a beer, it could be added to a lager which has been fermented with low fruity character and residual sugar, or it could be introduced to a beer fermented with a Belgian yeast that might leave residual sugar and a large amount of fruity esters.

In each situation, the same strain of Brett would develop different flavours at different rates. And this is where the dark art of making alternatively fermented beers really starts to come into play. There is no book that can tell you exactly how it will work or what you will get – you just need to try.

Pediococcus

Pediococcus the main lactic lactic-producing bacteria in lambic beers. It is generally more hop resistant than lactobacillus and is slow-acting too, so it has the unwanted ability to cause trouble as a hidden infection in breweries.

That said, the depth and complexity of the acidity one can obtain from pediococcus is said to be superior to that of lactobacillus, even if it does have the downside of sometimes making the beer “sick”. What I mean here is that when any refermentation occurs in the presence of pediococcus it can form exopolysaccharides (highly viscous carbohydrate polymers), which give beer a ropiness or thick/viscous/slickness.

This does break down over time in the presence of Brettanomyces but, my goodness, it’s a shocking thing to unknowingly put in your mouth – believe me, you’ll know if you’ve experienced it. It can be a real pain in the neck if you’re planning to release a beer that has been bottle-conditioning for three months only to realise it needs to wait another three months so it doesn’t feel like you are drinking snot.

On the plus side, many producers say beers that pass through this ropiness are far superior when they reach the other side.

Mixed Fermentation

Mixed fermentation in beer means just what it says: it’s the process of fermenting (or co-fermenting) a beer with two or more of the following yeast or bacteria types: lactobacillus, pediococcus, Brettanomyces, Saccharomyces, and kveik.

By developing or maintaining mixed cultures within their brewery, a brewer can generate a beer that is greater than the sum of its individual fermentation parts. Indeed, by varying the endless combinations of different micro-organisms, wort (the sugary water yeast turns into beer) composition, pitching rates (how much yeast / culture you add to the wort), as well as the duration and temperature of fermentation, the brewer is able to create beers that cover the whole gamut of the flavour wheel: from tart to sour, fruity to savoury, bright and simple to layered, complex and evolving.

This is also a technique a brewer can use to generate their “house flavour” – one that creates a common thread between their beers and can lend them all a unique and distinct character.

Further Reading

This is the section where I normally set some beer-drinking homework. It’s going to be a tricky one and maybe more of an extended holiday project this time around, however, as the yeasts/microbes I have written about – and, thus, the beers produced with them – are not so commonly available.

Lactobaccilus

Kettle soured beers are widely available so pretty much grab anything that says “SOUR” on it at the bottle-o and you will be in tart-puckering heaven.

Saccharomyces Farmhouse Beers

Kveik seems to have had its day, for the most part, but there are still brewers having fun with it. Keep an eye out for beers labeled Nordic or Scandinavian farmhouse. Shapeshifter have a cracking Nordic IPA.

Lachancea

The most common commercially available strain is Philly Sour so keep your eyes peeled for something like that on a tasting note. Or, better yet, at the next brewery you visit, you can ask: “Is this a lactobacillus or lachancea-soured/Philly Sour beer?”

I do know that Tristan at newly-opened Yellow Matter in Adelaide prefers Philly Sour for his tasty session sours.

Brettanomyces x Mixed Fermentation

Try drinking natural wine. Hah, I jest…

While there used to be a significant lack of mixed ferm offerings in Australia, it seems like a lot of brewers have been bitten by the bug and are now using multiple bugs in their beer (mixed ferm joke).

Check out Holgate’s trophy-winning and aptly name Sour Brett Ale, which uses lactobacillus and Brettanomyces. With a bit of a shameless plug and insider information, I can also share that all of Molly Rose’s sours are mixed ferm: I use lacto and saison yeast in quicker, cleaner ones (like our Raspberry Lamington Sour); for our longer-aged, bottled beers, they're fermented with our house culture of Brett, wild yeast from fruit, and lactobacillus.

Spontaneous

I think this could be a fun experiment. Grab a bottle of each of the following and take your tongue and internal microbiome for a spontaneous holiday around the world. It will take a little hunting, but it'll be well worth the endeavour!

- Spon by Jester King in Austin, Texas

- Coolship by Allagash Portland, Maine

- Beatification by Russian River Santa Rosa, California

- Village by Wildflower and Mountain Culture Katoomba, NSW

- One of La Sirène's Coolship series, Reservoir (formerly Alphington), VIC

- Chance, Luck and Magic Garage Project, Wellington, NZ

- 3 Fonteinen Beersel, Belgium

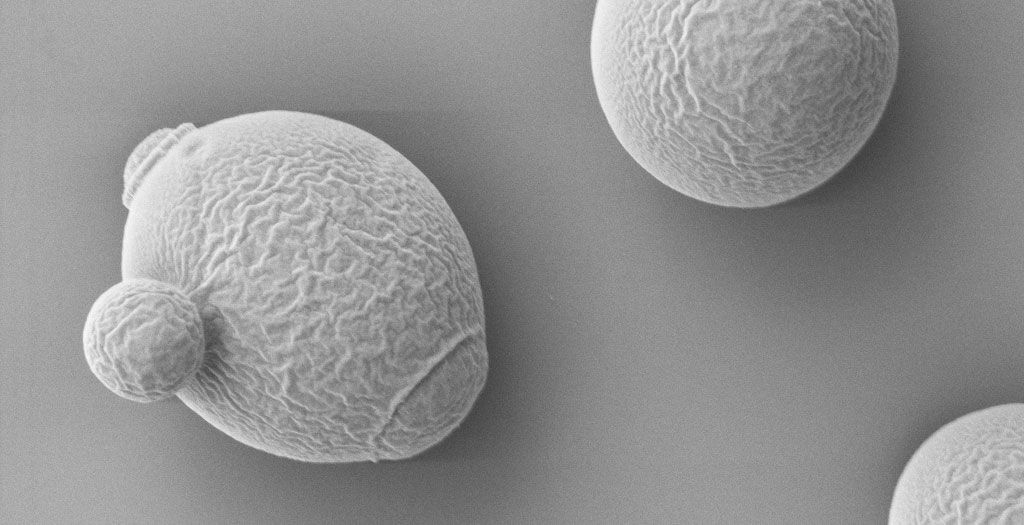

Photo of yeast starters at top of article from Drew Coleman at Watsacowie Brewing.