Last year, the world’s largest beer company, Anheuser-Busch InBev, merged with the second largest, SABMiller. It was the biggest deal the beer world has ever seen. In fact, at greater than USD$100billion, it was among the largest acquisitions in history in any industry.

For the average Australian craft beer drinker the news was peripheral, reserved more for the business pages of mainstream media and trade magazines speculating what the move might mean for market dominance of the country’s two main brewers: Lion (owned by Japan’s Kirin) and Carlton & United Breweries (CUB) which, by virtue of its ownership by SABMiller, would be absorbed into the new entity, AB InBev.

In recent weeks, however, the worlds of Big Beer and Australian craft beer have intersected. And the meeting point is an unexpected one: a Chicago brewery called Goose Island. It is a jewel in the crown amid AB InBev’s growing collection of craft breweries around the world and the one leading their charge to develop a global craft beer brand. Having already established a footprint in Europe, South America and Asia, Australia is next on the list.

Goose Island is far from the first American brewer to enter the Australian market. It is not even the first American brewer to have its beers brewed locally under license. Nor are the beers it is launching with especially unique in the current context of the local market.

Yet the nature of Goose Island’s arrival in Australia ensures it stands apart. It is a story that inhabits the frontier for beer today, where big, small, craft, corporate, independent and multinational coalesce into ever more shades of grey.

As Goose Island prepares to launch its flagship IPA in Australia, Nick Oscilowski ventures inside its Chicago headquarters to discover how and why it is being developed into a global brand, we find out what the plans are for Australia and gauge reaction from the beer world both here and overseas.

PART ONE: FROM GOSLING TO GOLDEN GOOSE

It was early on a Monday morning and I was standing on a Chicago street corner, feeling like shit. I knew it was nothing serious, just the inevitable comedown from a twenty-something hour flight, but that made no difference. My mind was still somewhere up in the clouds.

I’d decided to try and shake off the lag by getting some fresh American air. I ended up shuffling my pale zombie shell for the best part of an hour through streets that were very long and ominously devoid of people. In truth I was never alone – for company I had that shadow of anxiety which stalks you through unfamiliar streets in a city with an unenviable reputation for street crime and drive-by shootings.

The walk was meant to make me feel better. All it did was make me late. None of this was ideal preparation ahead of a serious interview.

There had been no specific request for the interview to be serious but certain things can be taken by implication: when a branch of the world’s biggest beer company offers to fly you halfway around the world you’re not there to talk about the weather.

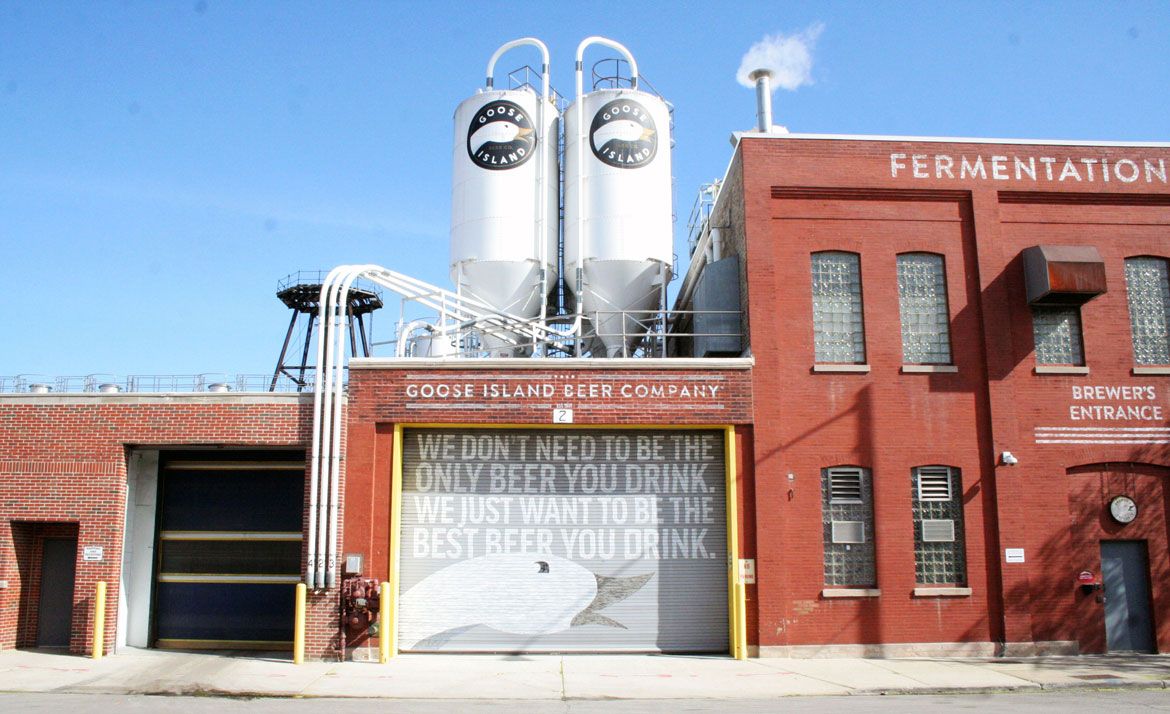

Turning and walking past a seemingly endless row of red brick buildings on Fulton Street, I reached a roller door emblazoned with a slogan: “We don't need to be the only beer you drink. We just want to be the best beer you drink.” It’s a clever line, part community-minded marketing pitch and part quality-driven mission statement. More importantly, standing in front of it meant I’d arrived at Goose Island.

For several years, to talk about beer in Chicago was to talk about Goose Island. Chicago today is a great beer city – its wider metropolitan area is home to some 170 breweries – but when the original Goose Island brewpub was opened by John Hall in 1988 you could count the number of local breweries on one hand. In the following years, that small number dwindled further until it was just Goose Island left drinking alone. For a long time its output remained comparatively small but its impact would prove disproportionately large as the brewpub became the epicentre for beer lovers in the city and put Chicago on the American beer map.

Some time in the early to mid 1990s (conjecture remains as to the exact year), they reached a milestone 1000th brew and wanted to do something a bit special for the occasion. They weren’t to know just how special it would become.

The short version of the story is that they threw a batch of beer into bourbon barrels and changed the way people viewed what beer could be; if you've ever enjoyed a barrel aged imperial stout of any sort, trace its lineage far enough down the line and there’s a good chance you’ll end up at Goose Island’s Bourbon County Stout. When you first started seeing footage of people lining up outside a brewery for 36 hours, in the freezing cold, to try to get their hands on a beer, this was what they were after.

The Bourbon County experiment, which began with a handful of barrels, grew exponentially to incorporate many more beer styles and become one of the largest programs of its kind in the USA; they keep the specific numbers close to their chest, but currently their vast Chicago warehouse is home to somewhere in the region of 15,000 barrels of beer. To give that some context, the Barrel Room at Australia’s foremost barrel ageing brewery, Boatrocker, houses around 300.

Shortly after Bourbon County's arrival, Goose Island opened a production brewery that took the company to another level, and things have only progressed on an upward trajectory from there. The core beers have won accolades with free flowing regularity; their flagship IPA, as the company is proud to tell you, has won six medals at the Great American Beer Festival, a competition at which medals are difficult to come by and in which IPA is one of the most fiercely contested categories.

Their Belgian-inspired range was pioneering in its own right, with the brewery being one of the earliest in the US to make use of Brettanomyces, wood ageing, fruit and souring to create beloved beers like Sofie, Matilda, Juliet, Lolita and Madame Rose – all respectful homages to some of the great beers from the Old World.

Ever the trailblazer, in 2011 Goose Island sold to Anheuser-Busch InBev, the owner of Budweiser and countless other household beer names. Sales of craft breweries to corporate entities are a common enough occurrence these days, but Goose Island was particularly significant as it was the first to send shockwaves through the US beer industry. To the average American, a deal that saw a large and successful brewery sold to an even larger and more successful one would be viewed as little more than adherence to the capitalist dream. But, in the eyes of the beer cognoscenti, Goose Island had been bought by the devil and the great old enemy of good beer.

The sale served to drive deeper the fracturing of what was becoming an increasingly partisan industry, split generally between those who placed value on supporting a resurgence in independently owned breweries and those who figured it didn’t matter who made a beer, or where, just as long as it tasted good.

It says something of Goose Island’s unique position that, some six years after the sale, the discourse around it continues to run as hot as ever. Some have never forgiven them. Some swear they will forsake them forever only to be lured back year after year by the barrel aged beers. Others are just grateful to see Goose Island beer at their local, and it is there where the corporate influence has been most striking.

In 2016, Anheuser-Busch InBev, already a giant company, merged with fellow behemoth SABMiller to become the truly colossal entity AB InBev. This company is easily the world’s largest brewer, with some 500 beer brands in its portfolio and, by some estimates, responsible for brewing one in every three beers consumed on Earth. Within that family, Goose Island is one of the favourite children. And with that comes the perks.

During its independent days, even after multiple rounds of expansion, Goose Island could supply little more than its home market and a handful of neighbouring states. Since being plugged into the AB InBev network it has well and truly taken flight. Many of the core beers – in what is surely another dagger to the heart of the purists – are now made at the same immense breweries which pump out industrial lagers like Bud Light. But, in the grand scheme, provenance of a handful of beers is secondary to what happens at the other end of the chain.

When a beer rolls off the line at an AB InBev facility it goes into vast distribution channels that carry it to all 50 states, from Alabama to Alaska. Goose Island is now able to export overseas at scale while backing it up with presence on the ground; in the last six months, Goose Island brewpubs have opened in London, Sao Paolo, Shanghai and Seoul – and more will follow. Through AB InBev, Goose Island has an enviable amount of technical and physical resources as well as access to every market in the world. Those are the key reasons many in the industry are predicting it will soon become the world’s biggest craft beer brand, even if, by the US Brewers Association’s definitions, it is no longer a craft brewer.

Which brings us back to the reason for standing outside the brewery in Chicago. Later that week, Goose Island would be releasing its first beer in Australia. The president wanted to talk.

PART TWO: THE AUSTRALIAN STORY

A 20 year veteran of the beer industry, Ken Stout has been with Goose Island for just under half of them. A few years after the sale to AB InBev, he became head of the flock as Goose Island’s President and General Manager.

A very tall man, he had to stoop a little as he poured a clutch of beer samples from six unmarked taps. The bar we were in is called the Tap Deck and sits on a small platform elevated above Goose Island’s Fulton Street brewhouse. Aside from the odd tour passing by, the bar is not open to the public. It is an area reserved for the brewers, a place to taste new recipes, get feedback on old ones being tweaked or just for tapping something interesting from Goose Island’s back catalogue. It was loud up here with the brewery humming away in the background but Ken’s deep voice carried easily above the din.

“This is the house beer we brew for the Chicago Cubs – you know, the baseball team – and it’s called 1060, which is the address of Wrigley Field. It’s just a nice Belgian witbier with some soft notes of coriander,” he said, before taking a sip and pausing abruptly.

“No, wait, this is not the 1060. This is, let's see… a bourbon barrel aged Belgian strong ale. Sorry about that. I didn't think that’s how we’d be starting the day! But, wow, that’s nice.”

It was. And, in its own way, it was an ideal eye opener as to the possibilities that exist by being Goose Island; there aren't many breweries where you have the opportunity to mix up a beer made to pour at the stadium of one of America’s most famous sports teams with an 18 month old barrel aged beer tapped just to see how it was developing.

On the very last tap in the Tap Deck that day was a four-point-something percent ABV session IPA called Midway. It was just a small batch, the remnants of a trial done some weeks before. The scaled up version had already been made, but not in Chicago. It was brewed nearly 10,000 miles away at the Cascade brewery in Tasmania (that brewery having become part of the AB InBev family following the SABMiller merger). Midway is not a beer Goose Island brews regularly in the USA but it was deemed to sit within the right boundaries of flavour and alcohol to be a good candidate for certain overseas markets. For Australian drinkers, Midway would be their first taste of Goose Island.

At this point, those uninitiated in ways of the contemporary beer world may raise an eyebrow when considering the situation whereby a Chicago brewery, owned by a multinational, is brewing its beer in another country but ostensibly still portraying itself as a Chicago brand. This is less to do with tricky marketing than it is grounded in the realities of brewing for multiple markets and wanting to put forward a quality product, something Ken is open about.

“We're brewing at Cascade because, for our more conventional ales and lagers, freshness is paramount. Travelling halfway across the world is not good [for them],” says Ken.

“For some of our barrel aged beers or bottle conditioned beers, those develop in the bottle and have a five year shelf life so, from that point of view, it’s going to be better for us to export those beers.”

From a quality perspective he is entirely right. Yet people will still point to provenance and ask whether a beer brewed under license can ever truly be the same as the original. Again, Ken answers frankly.

“We’re brewing there absolutely according to our specifications. We’re using different equipment but it’s Goose recipes, Goose ingredients, Goose process. Those beers are Goose beers,” he says.

“When they [the Cascade brewers] start to run trials on our recipes, they might not hit it on the first trial, but because they’re so good at hitting specs – the QA [Quality Assurance] and QC [Quality Control] – once they dial it in and get it right, it’ll be right every time. These are the same guys making light lagers and those are the toughest beers in the world to make. There’s no margin for error. They know how to hit specs and get the beer right, so it’s an advantage as it’s fresher and, with beers with some hop character, the fresher the better.”

During this bedding-in period, Goose Island’s Chicago-based brewmaster Jared Jankoski travelled to Cascade for the brewing of the first beers – and the subsequent dumping of batches that weren’t deemed up to standard. Since then the beers have been, to borrow Ken’s parlance, “dialled in” and given the green light to go to market: Midway was released in April and Goose Island IPA is due to hit taps from next week.

Overseeing the process of getting both beers into venues will be the newly formed Beer Collective within CUB. One of their signings is Beer Ambassador Tiffany Waldron, someone well known in beer circles thanks to her involvement in the likes of the Pink Boots Society and Melbourne beer bar Two Row (now Slowbeer Fitzroy).

“A lot of my role is teaching and training sales people, who previously may not have understood how important tap diversity is, about beer styles and how beer should taste,” she says of her mission to help educate staff and customers of a brewing company that has, for the most part, allowed craft beer’s recent explosion in Australia to take place without it.

“As the biggest beer company in Australia, we should be leading beer education in Australia.”

With the arrival of Goose Island, Tiffany and her cohorts have more tools with which to educate as well as the potential to put a quality IPA on tap in venues that would never previously have had access to such a beer due to their exclusivity arrangements with CUB.

“There’s a lot of CUB venues that are really excited to have the opportunity to have more diversity on their taps," says Tiffany. "IPA is the biggest growing style in America by a long way. It’s not like that in Australia yet as, in the wider beer world, people are still drinking a lot of lager. Having a consistent, well made IPA will really help that.”

So, while the initial focus is “on keeping it small right now” and supporting venues that “are taking good care of their lines and serving beer the right way”, she says: “The people who own the big [pub] businesses are having conversations with CUB and are excited about craft beer. We can lead with a good IPA that people know and love.”

PART THREE: BREAKING UP IS HARD TO DO

Loving beer has become complicated.

On that first day in Chicago, walking back from the brewery to the hotel, I passed a craft beer bar. I was tired but, after a day of interviews, an opportunity to wet my whistle wasn't going to be shunned. I parked myself at the bar, ordered two small beers of the barkeep’s choosing and struck up a conversation with the man sitting next to me. It became clear he was a Chicago local and knew about beer so I enquired as to his thoughts on Goose Island.

What unfolded was a love story. Yes, Goose Island was important to him and he used to drink it a lot. But when the brewery sold he felt betrayed. From then on, whenever he saw the IPA or pale ale or wheat ale at bars he spurned them – with all the new breweries in Chicago, who needed Goose Island anyway? But his old flames Sofie and Matilda and Lolita, they were seductive. He openly admitted to an annual affair with Bourbon County Stout.

This man couldn't quite let go. He wanted to end it but there was still so much to love. What made it harder was that he encountered it everywhere he went: sports bars, stadia, airports, chain restaurants, concert venues.

The ubiquitousness of Goose Island in Chicago post-takeover became a common theme with everyone I spoke to, whether they drank beer or not. It was true, some said, that many specialist beer bars had dropped Goose Island beers from their menus, but the lost volume was picked up elsewhere in the city and, increasingly, across the country.

The same story could be applied to a brewery like Mountain Goat. There are many in Australia who swore blind they’d had their last beer from the Melbourne icon once the sale was agreed with Asahi; many pubs dropped them instantly – some with a dose of public shaming, for added effect – and haven’t returned. But how many drinkers will have been tempted back by the likes of The Zymurgist or Pulped Fiction, crowned Champion IPA at the Australian International Beer Awards in 2016 and 2017 respectively? And these waverers, don't forget, are people living in the heart of the craft beer bubble.

“The reality is most consumers don't know or don't care,” says Eric Ottaway, CEO of New York's Brooklyn Brewery, which pre-empted Goose Island in brewing its flagship Lager with an Australian partner, in Brooklyn's case Coopers.

“Sure there are the passionate beer geeks for whom these big brewer incursions into craft are anathema to their existence, but that's a pretty small segment. For most consumers what's important is the quality and taste of what's in their glass.

“In many cases with big brewer partners, craft brewers such as Goose have been able to improve their quality so the consumer benefits. For those who don't care, they are getting a better glass of beer, for those who do, there are plenty of other independent options.”

PART FOUR: THE 96 PERCENT

There has long been an argument that craft brands owned by multinational brewers are, on balance, a force for good. They have the reach and marketing power to potentially lure more drinkers away from big brand lagers – even if the money often still ends up in the same owner’s pockets – and then, maybe, into ever craftier waters. According to another American brewer fresh into Australia, Firestone Walker, the push by AB InBev and Goose Island to become a global brand is doing this on a grander scale.

Adrian Walker is the brother of brewery co-founder David Walker and also the Californian brewery’s Export Director. He was in Australia to launch the brand, which merged with Belgian beer conglomerate Duvel Moortgat in 2015, during Good Beer Week last month.

“Maybe somewhat controversially, last year I launched [Firestone Walker] in Korea,” he says. “The week before I got to Seoul, ABI had been there with Goose Island and spent USD$1.5million. The whole place was pumping for craft beer so away we go. The furrow had already been ploughed.

“If we want our message to get to the 96 percent, we need to start ploughing some very large fields and, in order to do that, we need some very deep pockets. As much as I understand the pain and anguish that these small breweries have been gobbled up by some Goliath, if you step back and look at it pragmatically, if you want the world to turn onto craft beer, someone has to find some money.

“It’s trying to find that balance. It’s not different to any other industry; look into any other one across the pantheon of retail domains and it’s always happened.”

Many would argue that CUB has long had the products and, on an Australian scale, the means to win over the 96 percent. Yet, prior to the most recent change of ownership, the winning over has been left to others.

“It’s a bit of a slap in the face for everyone that has worked across the Matilda Bay business over the years, but I guess that’s change and progress,” says Stone & Wood Brewing Company co-founder Brad Rogers of the impetus being injected into Goose Island via CUB.

“How would those guys feel? There’s a lot of people in there that are charged with running the Matilda Bay business and brand. It seems like they’ve let some of those older brands dwindle.”

Matilda Bay is, of course, one of Australia’s iconic craft beer brands. Born in Fremantle in the mid 1980s, it has become something of a forgotten hero, shunted down the pecking order as CUB’s focus within craft has switched to Fat Yak and its Yak Ales brethren.

Brad is one of three founders of Stone & Wood, all of whom worked at Matilda Bay in various roles before setting out on their own path in 2008. He was the head brewer when CUB brought the WA operation to The Garage brewery in Dandenong, creating, among other beers, Australia’s first commercially released saison, Barking Duck, and Alpha Pale Ale, the beer named Champion Australian Beer as recently as 2013.

Given his past and the runaway success of Stone & Wood, he’s well placed to comment on current moves and questions whether his former employer can adjust to a sector of the beer world that has changed rapidly since Matilda Bay was last a name to excite Australian drinkers.

After all, as recently as July 2015, CUB’s Head of Brands – Craft and Australian Premium, Tim Ovadia, told Australian Brews News: “Do I think that a plethora of extreme craft beers with high BUs and super-high hoppiness levels have limited appeal? Yes – that’s not an opinion, that’s a fact. It’ll never cross over to a broader group.”

Brad draws a comparison with the other major player in the Australian beer world.

“Look at the way Lion has treated the length and breadth of craft here and now in New Zealand – they seem to have left people to run the race,” he says. “What they’ve been able to do with Little Creatures has been quite respectful. When you take a step back [and look] at what CUB has done with developing the sector and the beers and the people in their business, you’re left wondering.”

He adds: “Maybe now, with the managers across SABMiller and now AB InBev, there’s got to be some smart people in there that have come with experience. A lot of what they are bringing is experience of what they’ve seen in the US. Whether that translates in a similar way in this country remains to be seen.

“Maybe this is the ABI angle – to inject a bit of enthusiasm into their craft portfolio.”

That’s certainly how Tiffany sees it.

“Being part of ABI is a big difference,” she says. “The change of ownership has meant there’s a lot of excitement in the office for the things we’re able to do. We were at GABS opening the sour vintages and, having that for our senior management and CEO to taste – they’re seeing people get excited about these beers.

“Matilda Bay is still being made. It’s still loved. [We] just haven’t put a lot of investment into making it what it was. A lot of that was the old ownership. The new ownership wouldn’t have let [Matilda Bay’s slide] happen. You can look at what they’ve done in America. They’ve invested so much into craft.

“CUB has a new mob. We are part of this much bigger, broader family.”

One, she points out, that has encouraged moves such as a recent barrel aged collaboration with one of Australia’s most respected small breweries, Boatrocker, during Good Beer Week.

“My boss asked me in my first week [what I’d like to achieve] and I said I’d like to see IPA at the MCG,” says Tiffany when asked how far she’d like to take the brand. “He made a face at me and said, ‘At least you have goals.’”

PART FIVE: SMALL BEER

Grant Wearin is co-owner of another respected small Australian brewery. Modus Operandi launched with a bang, sweeping the board at the inaugural Craft Beer Awards months after opening its Northern Beaches brewpub, and has continued to collect awards and receive critical and public acclaim since. He and wife Jaz spent time studying the US market before opening their Sydney brewery and have a former Oskar Blues man as their brewer too.

While it’s early days, he sees potential dangers ahead for small brewers – above and beyond those already faced in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

“It has the potential to be a dangerous game when venues are accepting free kegs to launch a product that they haven’t previously been affiliated with,” he says in the wake of Midway IPA’s launch.

“Take a cynic’s mindset: the benefit for CUB [in donating free kegs for launches] is it costs less than $100 to introduce that brand into what’s previously been an independent venue. Consumers might assume that it’s an independent product as that’s all that venue has ever served. It’s a dangerous game rolling that forward to its logical conclusion, which is blocking competitors out.”

He references tap contracts, the contentious issue that looks set to come to a head soon. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) should finally announce its findings from a multi-year investigation into practices by the major breweries in the coming weeks, while a legal firm is looking to launch a class action suit on behalf of small, independent breweries.

Grant believes “a lot of [CUB’s] customers are crying out to renegotiate their contracts as consumers’ tastes are changing faster than CUB’s product portfolio. [Goose Island beers] might satisfy those places calling for something else as they slot that new beer into an existing agreement, thereby continuing to stifle market access.

“It’s a defensive move to protect turf they’ve invested in and that’s not something that smaller breweries have the ability or access to do. It’s a portfolio balancing question.”

One of the six venues in Melbourne and Sydney chosen for the Midway IPA launch events was The Catfish, an award-winning craft beer bar in Fitzroy. Co-owner Kieran Yewdall admits they’d “never, ever, ever” had a CUB beer on tap before the launch, but he backed his bar manager’s decision to become a launch venue when approached by Goose Island’s representatives.

“As a venue, we’re looking forward to seeing some of the other Goose Island stuff, like the barrel stuff, hit the shores,” he says, suggesting that, if done properly, the arrival of brands like Goose Island – and the many other large and reputable American breweries entering the local market – could bring rewards for the broader beer scene.

“It could herald a golden age now that international breweries understand that we have the ability to produce what they want to produce here,” he says. “When I first started drinking beer, I used to think North American beers were all like Labatt Blue and I thought that was excellent. Now I know better. But will they think that's what the Aussie drinker wants? Will they make beers like that for this next generation?

“If they’re going to only produce easy styles, much like the mass brewed stuff that's here already, I’d be very disappointed in what that does to the brand. Everyone knows and likes Goose Island but if they only produce stuff an accountant or marketing person thinks the market wants then they will sell a lot in big chain bottleshops but won’t make any traction in the good beer world. If they try to showcase what that brand is, more power to them.”

At this stage, The Crafty Pint is unaware of any firm plans to introduce more Goose Island beers here beyond the two IPAs. There are bottles of iconic releases such as Matilda and Sofie that will appear at special events and the aforementioned collaboration with Boatrocker is set to be launched later in the year. That said, while nothing has been publicly confirmed, the way the brand has been launched in other markets would suggest a Goose Island brewpub in Australia is likely. Indeed, according to Ken Stout, “it’s very possible”.

He said: “We have to get acquainted first with the market. We don’t want to be a part of the Australian beer market and assume too much or push too hard. We have to support it, educate and make friends, but we have to do it in the right way.

“We’re not there to encroach on any other brewery’s business, per se. We think the rising tide will lift all boats.”

PART SIX: INTO THE UNKNOWN

I was getting on well with the guy in the bar, the one with the old flame he couldn’t quite extinguish. He told me he travelled all around America for work and frequented a lot of beer bars but that his favourite was right here in Chicago – just around the corner, in fact. He proposed we finish our drinks and head there.

His car was parked just outside. We got in and he started the engine. That was the precise moment my old companion, the shadow of anxiety, who had disappeared during the day, came roaring back into being. It was dark and I’d gotten into a locked box on wheels with a large man I’d just met and knew next to nothing about – not even his first name. I’d soon be lost. I had no phone. No one knew I was here, heading into the unknown...

In the beer world today, there are plenty of unknowns. That’s only natural as craft beer becomes increasingly global and local at the same time and everyone within it tries to work out their place in the evolutionary process. Surely, I thought, the man at the head of a business looking to drive beer into new frontiers would be able to unravel some of these unknowns. So I asked Ken.

“At a recent panel I was asked, ‘What’s your prediction in the US in the next five years?’,” he said. “My answer was, ‘I have no idea.’ There are good guesses, but the ways things have changed so much, I really don’t know what it’ll look like.

“There are so many breweries opening now and people are saying, ‘How many can the United States support?’ Right now there are 5,300 and there are two opening every day. That’s 5,300 right now and 2,000 in planning. So, for the next thousand days there’ll be two breweries opening a day.”

If you wanted to shake up an already competitive industry, adding another 2,000 businesses to the mix ought to do it. The flow-on questions facing the industry are seemingly endless.

Will there be a fuller embrace of hyper-localism, where drinkers are not simply loyal to a brewery in their state or city, but to one in their neighbourhood? Will the multinational brewers ever find a level of contentment, or are they obliged by their nature to swallow more breweries in order to feed an insatiable appetite for market share? Will competition from above and below squeeze well respected brands out of the market they, in many cases, helped create? And, considering how often it is said to follow the American industry, what on earth might all that mean for Australia down the line?

“I don’t think anyone does really know,” says award-winning Melbourne based beer writer Luke Robertson of Ale of a Time. “You can look at history and how it ebbs and flows but I think we’re in a new market now so it’s hard to look at where it could be in five years. Everyone has to wait and see.

“Some people, whether they’re Australian or American brewers, probably aren’t going to come out unscathed – that’s my concern about some breweries I really like. Every second person I know says they’re going to open a brewhouse then open them across the country and I don’t think that’s going to work.”

He wonders, too, whether some American brewers have “left their run a little bit too late”.

“Some years ago, Firestone Walker or Lagunitas arriving here would have been really exciting. They’re saying their beers will be here in a month [from being packaged], but I can walk to my local brewery and get something fresh off the tap. I don’t know if American beer really has the cachet it did five years ago when Sierra Nevada launched. Then it was ‘Wow!’ as it’s an icon, but we are building our own icons now: Boatrocker or La Sirène or Modus Operandi – people are excited by these.”

In Goose Island’s favour, however, he says: “They have the money to find out how it’s going to pan out.”

Speaking of seeing how things would pan out, me and my nameless companion made it to the bar without incident. It was called The Map Room and, like Goose Island, is a stalwart of the Chicago beer scene. The place appeared timeless but, for more than two decades, it had been moving with the times, remaining at the forefront as the city’s tastes had changed. You could sense there was real history and a real story here. Plus it had a menu that would make a beer geek quiver. I could see why my new friend liked it.

We had a beer. We had a couple. I probably had a couple too many.

He left and drove home. I stepped out the door, back into the unknown.

It was late on a Monday night and I was standing on a Chicago street corner, feeling fantastic.

In part II, we attempt to further unravel the unknowns in a look at the American and Australian craft beer industries: their rises, their falls, where they are today and where they – and craft beer globally – are headed.

About the author: Nick Oscilowski lives on the South Coast of New South Wales and writes about beer. He has nothing to complain about. Well, he never used to but, having travelled to Chicago as a guest of Goose Island, now has to readjust to a life flying cattle class again.