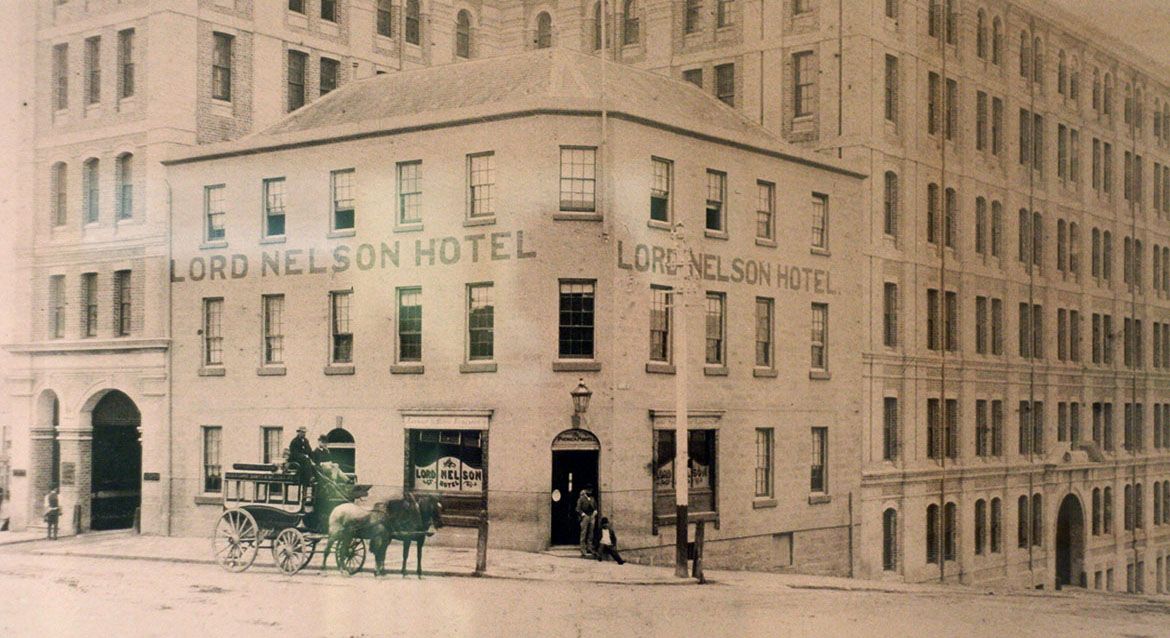

In 1986, Blair Hayden, as part of a consortium, did something fairly unremarkable: he bought a pub. It was in The Rocks, the area where Europeans first settled in Sydney and which is now arguably Australia’s most photographed suburb; this is the point where the city’s sublime Harbour Bridge begins arching northwards and, in tandem with the inimitable Opera House, forms the most iconic of cityscapes.

The pub itself was slightly run down but it had good bones, the thick sandstone facade forming the kind of enduring, imperious character of a building born at the height of Colonial Empire. In straight commercial terms, the site wasn't ideal, with the bridge funnelling commuter traffic straight past and the skyscrapers of the CBD sitting an awkward distance away for the legions of thirsty office workers. Still Hayden figured, if it was managed properly it had potential.

William Wells had once seen potential here too. It was in 1841, based largely on a clientele pooled from maritime commerce and the establishment of the nascent city, that this apparently hardened convict turned bootlegger turned plasterer transferred the license of his then pub, The Sailor’s Arms across the road, to his home which he had converted into a hotel. He named this new business The Lord Nelson.

Now, 175 years later, it is, famously, the oldest hotel in Sydney to still be operating under its original license and within its original framework. When Blair Hayden first approached the front door, some 140 years after Wells, it’s easy to imagine the weight of history making the keys sit heavily in the pockets of this untried publican. But Hayden was no shrinking violet.

A New Zealander by birth, his outward demeanour can come across as blunt and forthright. But, by way of endless anecdotes, often delivered with a healthy dose of profanity, it quickly becomes clear that behind firm principles there is a deep well of humour and ebullience perfectly suited to the position of publican. The role that had brought him to Australia, to Sydney, was meat trading – he had been posted from the UK to secure exports back to Europe. It was then that the opportunity to enter the pub game was presented.

As he recalls it: “A mate of mine, Duncan MacGillivray, did a thing called Two Dogs alcoholic lemonade and he said to me, ‘The Campaign for Real Ale [CAMRA] is going pretty well in the UK, why don’t we do something in Australia? I know a guy who’s got maltings in Adelaide. Let’s start a brewery’.

“Because we were grain traders as well as meat traders, we knew what was going on in the malt business, plus we got on well with the Cooper family. The Sail & Anchor had just opened in WA so we decided to get on with it too. Well, initially I said no as I didn't want to get into business with a mate, but he kept hammering on the door so I finally agreed and, with some partners, we got going.

“We looked at over a hundred pubs to find a site and eventually found this place. It was pretty run down and at the wrong end of town which meant you had to draw the crowds, but it was a destination point. We went ahead, took a bit of a risk, put in a brewery and the whole object was to brew ales and not to be taken to by the big breweries.”

The Australian beer landscape of the 1980s was dominated, in near totality, by the duopoly of Carlton & United Breweries and Lion Nathan. Tied houses, where one brewery effectively owned all the taps in a venue and retained exclusivity over what beer – or, more specifically, which lager – poured through them were beyond common. It was simply accepted practice.

Further to such tap arrangements preventing competitors from pouring beer, these companies were known to attempt to cut out the competition before it had a chance to get established; on occasion, when small breweries were taken over or upgraded, equipment was ordered to be destroyed which had the effect of killing off the second hand market. Such mandates give some sense as to how the beer business was run, with an eye for preserving the status quo, encouragement of voluminous swilling and informal gentlemen’s agreements between rival brands not to wade too far across borders and upset state-based beer parochialism.

With their own brewery – a second hand kit imported from the UK – The Lord Nelson would not need to acquiesce to the demands of any larger brewer.

“Right from the beginning we brewed beers that were different,” says Blair.

“I could give someone a Tooheys or a VB and I guarantee, with a blindfold, they would hardly know the difference. When people would ask for a VB and we’d tell them we don’t sell it, that we brew beer ourselves, you could see the perplexed look on their faces. They’d be like, ‘Sorry? What do you mean?’, and some people would just walk out.”

But a great many stayed. In doing so, they would be taken in by an ambience as close to the feel of a classic British pub as you will find in Australia. They would eat the kind of food that would sit under the gastro pub banner, several years before the term "gastro pub" was officially coined. They would enjoy the unique view of the inner workings of a brewery. And they would enjoy the beer.

The Beer

The opening salvo of Lord Nelson beers was a range of ales that traced its lineage, in style and name, back to the pub’s British roots and its most famous naval hero: Trafalgar Pale Ale, Victory Bitter, Old Admiral old ale and Nelson’s Blood porter. In a land where lager was king, there was very little else like these available locally: unfiltered and unpasteurised beers, full flavoured but all approachable even to the uninitiated beer drinker. These days you might call them session beers, a term now popular with craft beer drinkers rendered numb by an overdose of highly hopped American IPAs and who are returning to beers with more classic balance and moderate levels of alcohol. As is often the case, Hayden has a snappy line to sum up the Lord Nelson’s approach:

“If you don’t want two beers, you’re not drinking ours,” he says.

“They’re all sessionable and we want to make them that way. That’s my philosophy: that you’ve got to have beer people want to drink more than one of.”

That concept may not make The Lord Nelson’s beer particularly trendy in today’s rapidly evolving beer scene but, in the beer monoculture of the late 1980s and early 90s, it made them stand out. And, almost counterintuitively, it still does: as craft brewers have been busy chasing the next big thing, The Lord Nelson has simply stayed the course with its traditional ales.

You need little more evidence to convince you that this has been a successful format than to consider the beers first produced 30 years ago are still the ones being brewed there today. Of course, they are not exactly the same. No beer could be. So The Lord Nelson embraces those differences, however subtle they may be.

“We have such a high turnover that we get golden batches all the time, but that’s just the nature of the pub,” says Blair.

“A friend of mine drinks Victory Bitter and every time says it’s the best beer ever but I said to him, ’It’s had about 38 incarnations!’. It’s still Victory Bitter but a tweak of malt, or a different batch of malt, means you can’t quite get the exact same beer, but I think that’s exactly what it’s about.

“Brewing has similarities with winemaking, the difference is we’re doing a new vintage every week or every brew. Yes you can make very consistent beer if you go backwards and forwards with your process, but I don’t want to be like that. I’m happy and excited that it’s different to the last one.

"These days, with ales, people understand that that’s the way it is: whether it’s Summer, it’s Winter, maybe the malt’s not as fresh or the hops are at the end of the season – these are just variances you get.

“It’s always brewed to style, but if it’s a bit like this today or a bit like that today, so be it.”

The four core beers were soon joined by a fifth, Fleet Wheat. It is still one of the pub’s most popular, though it goes by another name and the story of how that came about is an example of the assurance with which Hayden and The Lord Nelson were travelling together.

Presidential Sweet

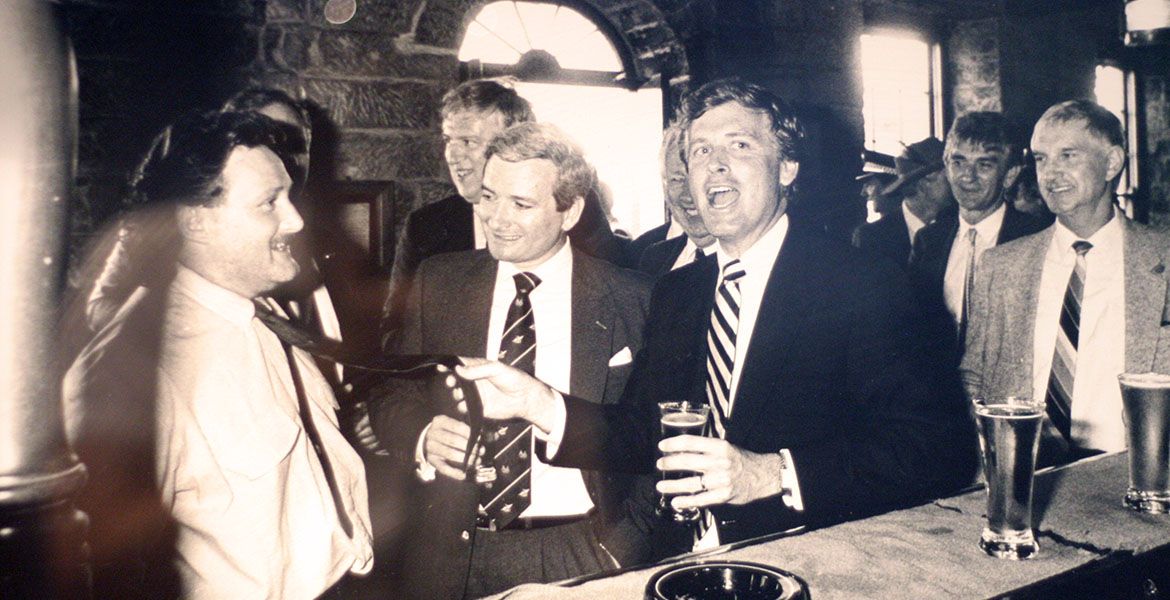

“Dan Quayle, the Vice President of the USA, came to the pub and had a beer,” says Blair.

”It was following all the bullshit around the wheat embargoes, with grain exported from the USA being subsidised and fucking the price for Australian wheat and barley around the world. Fleet Wheat was a wheat beer – well, wheat and barley – and he was yakking about that and I was giving him a bit of a hard time, saying, ‘Mate, let me tell you something: we don’t subsidise our farmers here, we support them. That’s different to you lot – you want to give them cash for nothing to keep them going but here we just get on with it with hard work. So much so, in fact, that we malted this wheat and made a beer out if it. That’s how we’re helping our farmers. You guys in the states should consider it too instead of trying to knock off the smaller people of the world’. It was all in good humour.

“Then I said, ‘Since you’ve been here, I’m going to name this beer after you’. I got a bit of chalk, went to the blackboard, crossed out Fleet Wheat, wrote Quayle Ale and said, ‘You can’t do that at a big brewery can you!’

“It must have been a slow news day with nothing else going on in the world because we hit the front page of the New York Times, London Times, Hong Kong – it obviously went out on Reuters, ‘VP Dan Quayle drinks at pub in Sydney’.

"Then the phone started ringing with Americans on the line saying, ‘You must be a fucking idiot to have Dan Quayle in your pub – he’s an asshole.’

"That was a bit of an insight into how passionate they are about politics because this went on for about a week.”

After Quayle Ale became a permanent fixture, it was more than three years before another beer was added to the ranks but it would prove to be a worthwhile wait. The idea came from Hayden’s broader interest in wine and was brought to life by American brewer John Clannon.

“When John arrived, I told him that we wanted to create a new beer,” says Blair.

“I wanted a Sauvignon Blanc beer, something with lovely floral aromatics and herbaceous characters on the palate, but something undeniably sessionable. We made it and put a competition out across the bar: a free pint and a smack around the ear if your name is selected. A guy came up with Three Sheets and it was perfect. It’s the only beer I didn’t name.”

Three Sheets, an Australian pale ale, would go on to become The Lord Nelson’s flagship beer.

The Brewery

The Lord Nelson, by its nature, is resistant to change. The building is protected by a heritage listing, which means the core of its structure, essentially the L-shaped main bar and the old walls that constrain it, is literally set in sandstone. It is quite obviously not a space built to house a brewery, so the fact that it does means it is one of the more unconventional setups you’ll come across in Australia: wood-clad tanks on the ground level connect downwards, through the floor, to the rest of the brewhouse, wedged into a warren-like series of subterranean rooms that seem only one rack short of being a torture chamber.

“There are hatches, which is how we get everything in and out of the cellar,” says Blair. “The criteria for everything in here is that it has to fit through those gaps.”

As you watch head brewer Andrew Robson scurrying up and down between levels to add hops or change a hose, you begin to appreciate that an extra degree of arduousness is automatically added to even the most mundane of tasks here – perhaps it is that extra effort which goes some way to explaining why The Lord Nelson’s beer always seems to taste better in the cosy confines of the pub? Yet, despite being hemmed in both physically and legislatively, there was enough wiggle room to expand, ever so slightly.

“We did a major renovation about 14 years ago where we knocked all the back of the pub down,” says Blair. “It was all gone.

“We had the tanks sitting outside and my son [Trystam Hayden, now co-founder of Brittania Brewing Co in Vancouver] was brewing and complaining like fuck because it was raining and there was rubble falling over, plastic covering the tanks and he’s saying, ‘I can't do this, I can't do that’, and I’d just say, ‘Shut up and get on with it, we’ve got no other option!’. But it really was a nightmare.

“[English beer writer] Michael Jackson came in after the renovations and said, 'Oh, the place has gotten bigger, Blair – I reckon by about four inches on that wall’. It was about a foot I think.”

As part of this “extension”, the brewery gained more tanks, which stretched its capacity as much as physically possible. That helped the bar keep ticking over and the hotel to continue to building on its legacy but, as a business, The Lord Nelson had effectively reached the limits of what could be achieved within its confines. If they wanted to grow, they would have to look for other ways.

“To expand the business, the only way to do it was to expand the brand,” says Blair.

That provided the impetus to start packaging beer. Installing a packaging line in the pub was, quite obviously, out of the question so they opted to contract out the brewing and bottling of their most popular beer, Three Sheets.

“The bottles only started seriously about five years ago,” he says. “It was very quiet initially because craft beer was still only just getting a bit of momentum then, but we chose bottles because I wanted to be in restaurants.

“I’ve always, for 30 years, talked about beer like wine – sniffed it, smelled it and have people look at me like I’m an idiot. But it’s important to me. And it was the sommeliers of Sydney that got behind us and helped push the word. That’s why we’re proudly associated with the Rockpools and Quays of this world; sure, there are others on their beer lists now but in the beginning it was us.

“Beer is becoming as important as fine wine and I think that’s one of the greatest things to have happened to the beer industry, and I’d like to think we’ve been instrumental in that because of the way we pushed the on-premise trade.”

The Next 30

As if to underline the point about beer and wine working hand in hand, Upstairs, The Lord Nelson’s first floor restaurant, was this year awarded Australia’s Best Pub Restaurant Wine List by Gourmet Traveller. As the owner of Lot 462 wines in the Barossa Valley, it was no doubt an especially pleasing accolade for Blair as well as an auspicious one to receive in a year that saw the hotel reach 175 years and the brewery celebrate its 30th, cementing its place as Australia’s oldest independent, continuously operating brewery.

Then, on the other end of the spectrum, this year has seen something new with the release of Lord Nelson beer in cans, the Quayle Ale and slightly un-Lord-like Backburner Belgian IPA. With all that has gone, it is worth asking how The Lord Nelson is likely to be approaching the future.

“We believe in what we’re doing so we’re just continuing in the manner we started,” says Blair. “That’s why the 30th Anniversary Ale was called Dead Ahead.

“Back in the beginning, [Malt Shovel founder and brewer] Chuck Hahn and I used to go to Canberra to try and get the beer excise tax reduced and they used to look at us like we were fucking idiots: ‘Craft beer? What’s that?'

"They didn’t know anything about it, they just didn’t understand. We were so far ahead of our time it was ridiculous really.

“But we’re seniors of the industry now and we’ve proven this business is sustainable, provided you keep to the parameters of your ability, and I think we've got respect from the industry for doing that."

From humble home to hotel to brewpub to national brand, The Lord Nelson has been and meant a lot of things to a lot of people over a long period of time. In 1986, fate determined that it was Blair Hayden that would be charged with steadying the course over the following three decades, playing the part of captain, publican and patriarch. But The Lord Nelson is more than any one person.

Hayden’s tenure was born out of several partnerships, some still going strong, others not. There are employees that have been there the whole time, several for more than ten years, some who do not need to work but still put in shifts because they love the place and because they’re a part of it.

Children have graduated from skateboarding around the old wooden floors and ordering pink lemonade to helping run the business and brewing the beer that is the pub's life blood. There is a group of regulars that has come every Thursday for 30 years. Others remain forever in spirit, despite leaving this world. The Lord has many sons and daughters and they are all part of a much bigger story.

As 2016, a milestone year for The Lord Nelson, comes to a close, the last word ought to go to Blair:

“We’re in hospitality and my brief has always been the same: be hospitable," he says. "That’s what it’s about and we’ve done it, I hope, with aplomb. Sometimes correctly, sometimes incorrectly, but everyone is welcome here and that has been the case for 30 years.”

With that in mind, given the chance, would he do it all over again?

“Fuck yes, without a doubt. This place is amazing.”

You can find The Lord Nelson at 19 Kent Street, in The Rocks.